“Quinquireme of Nineveh from distant Ophir,

Rowing home to haven in sunny Palestine,

With a cargo of ivory,

And apes and peacocks,

Sandalwood, cedarwood, and sweet white wine.

Stately Spanish galleon coming from the Isthmus,

Dipping through the Tropics by the palm-green shores,

With a cargo of diamonds,

Emeralds, amythysts,

Topazes, and cinnamon, and gold moidores

Dirty British coaster with a salt-caked smoke stack,

Butting through the Channel in the mad March days,

With a cargo of Tyne coal,

Road-rails, pig-lead,

Firewood, iron-ware, and cheap tin trays.”

CARGOES by John Masefield, published in 1902

Sailing the seven seas

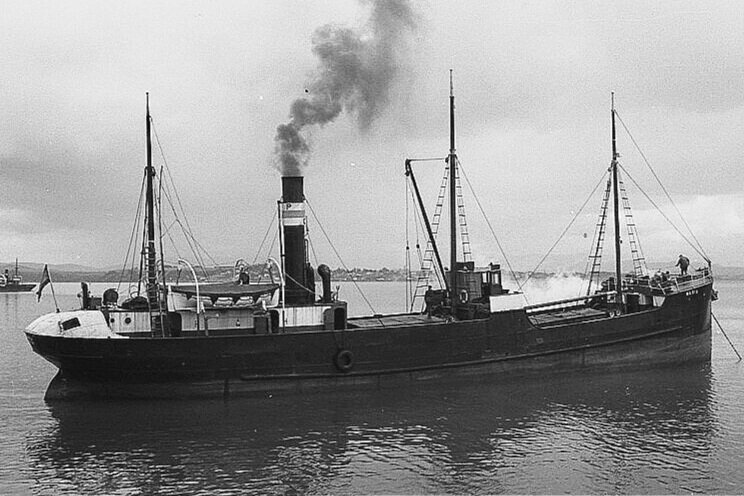

SS Robin in 1895 loading casked Herring at Lerwick, Scotland

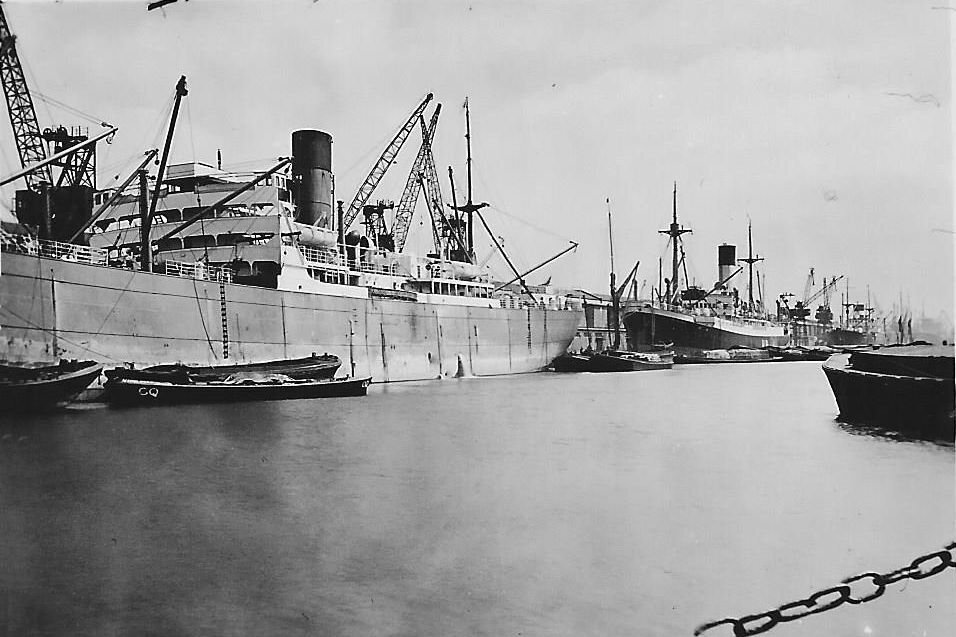

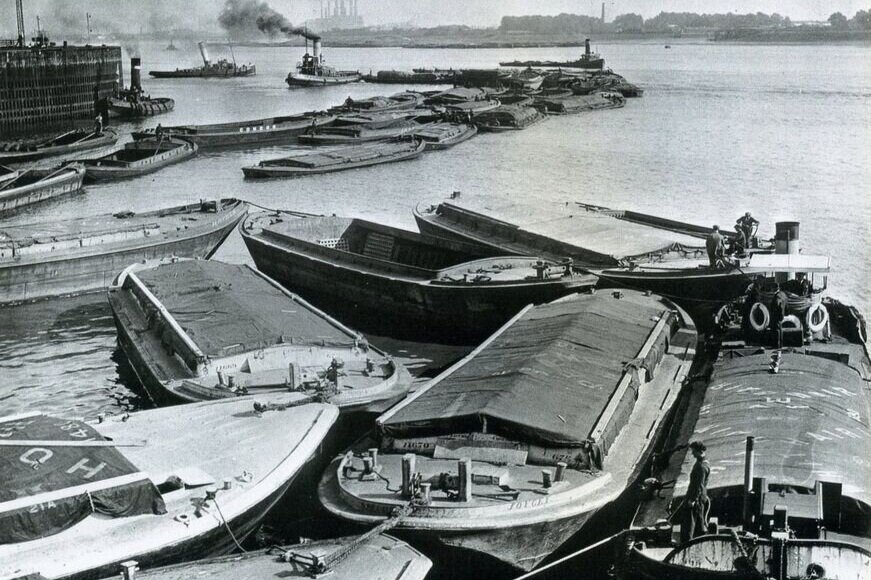

A workhorse of the late Victorian era, Robin in her day was a typical small sized coastal cargo steam ship or coaster, one of thousands of a family of cargo ships tramping their way around the world to far flung places, keeping close to treacherous shorelines or voyaging carefully over open stretches of hazardous sea.

Carrying general goods, raw materials, livestock, food and other commodities their design evolved from the small sailing ships they helped to replace, whose origins dated back to antiquity.

A life at sea in the 1890’s was an adventure at the mercy of weather, wind and tide. Navigating by stars and visible features on land, often without radio and with no other electronic aids, steamships like Robin sailed long days and nights at slow speeds giving uncertain arrival times at end destinations. Away for weeks, months and sometimes years from their home port their crews would either look forward to returning to their families and homes ashore or lead a seaman’s life with no ties or fixed abode. For many it offered a chance to see and experience the world in way that persons on land could only dream or read about. Ships such as the Robin became immortalized, celebrated and romanticized as a result.

Steam cargo ships, coasters and tramp steamers were as varied as their owners and the crew which sailed under them; most such as Robin were well kept, ordered and maintained to high standards, sailing coastal routes in sheltered waters to regular destinations, with larger sister vessels sailing in the same way but able to cross oceans and deep sea in all weathers voyaging around the world. Some such as tramp steamers lived for the moment, relying on their captains intuition in sailing to random ports in the hope that a cargo consignment could be won. Others could literally be floating death traps; ‘rust buckets’ or ‘coffin ships’ in shocking condition which had reached the end of their economic lives, beyond the reach of insurance inspectors and maritime law. Many were lost to poor weather conditions and heavy seas while others were deliberately overloaded, wrecked or sunk so that false insurance claims could be made.

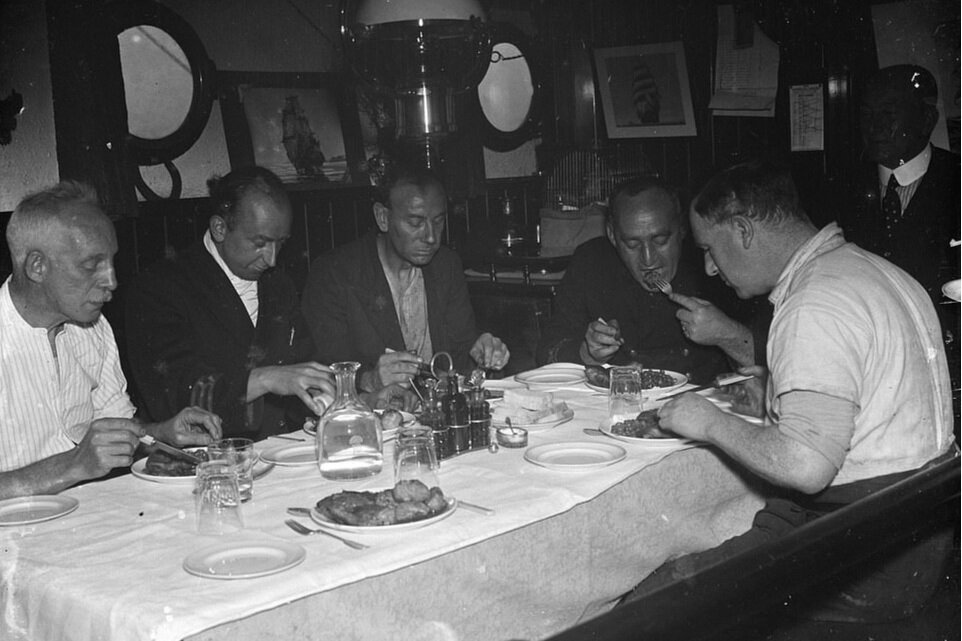

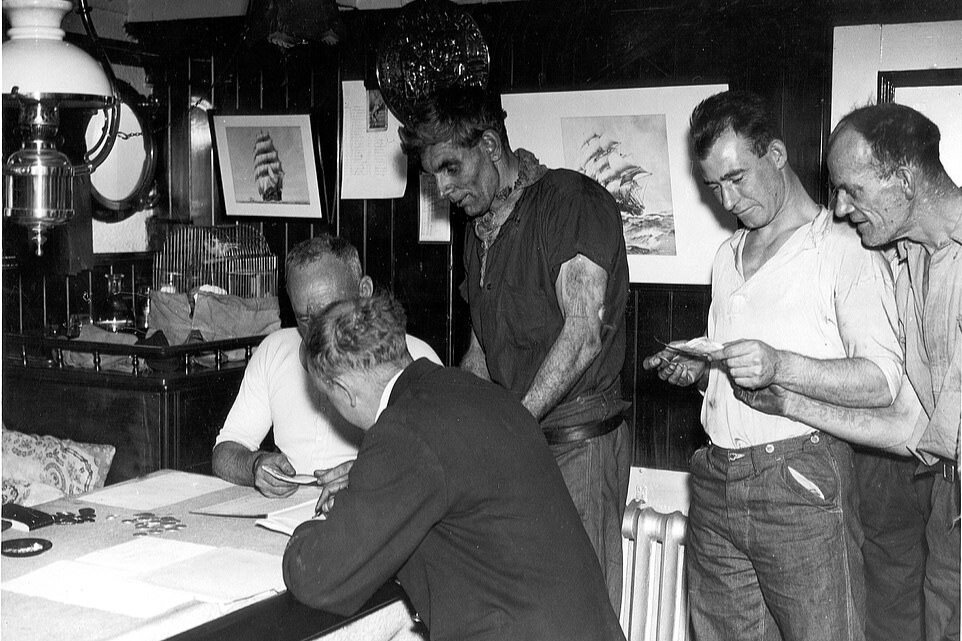

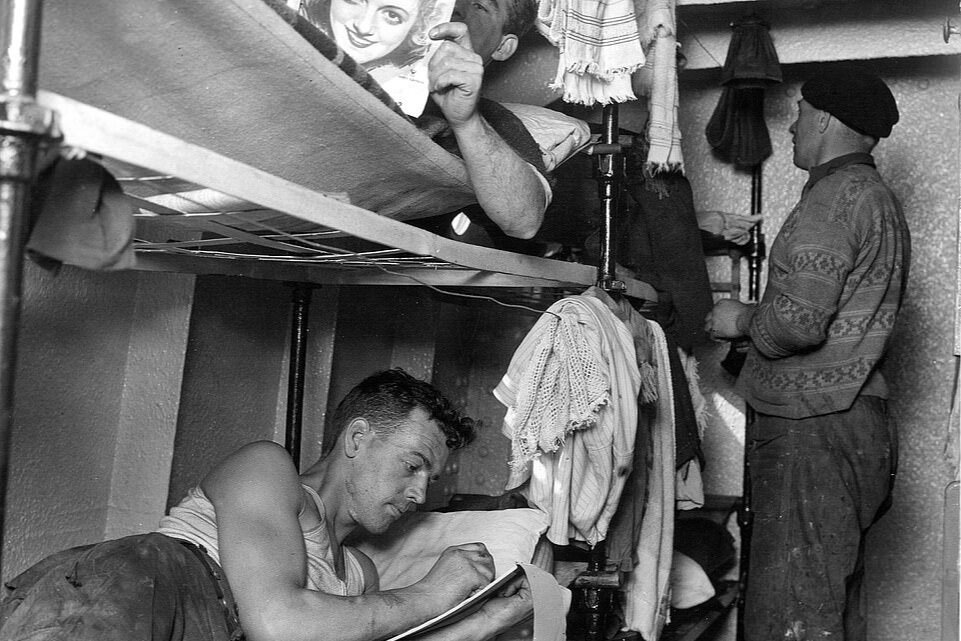

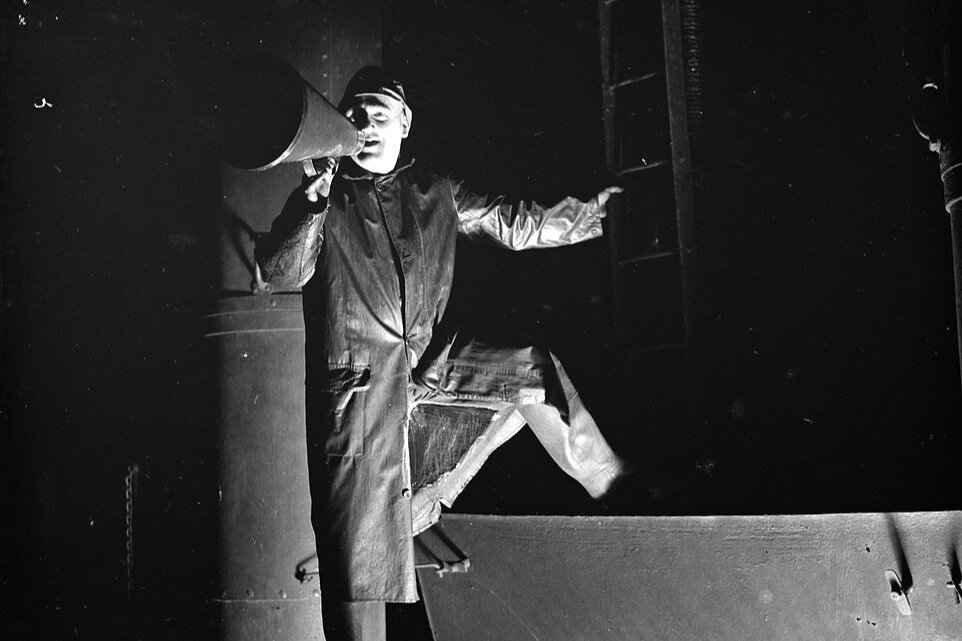

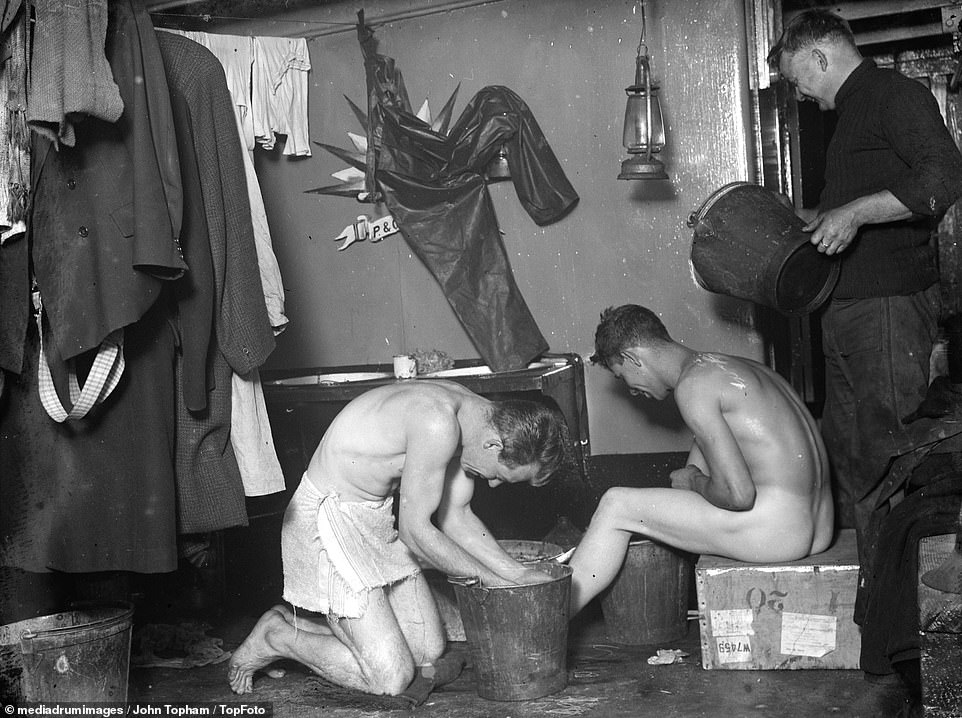

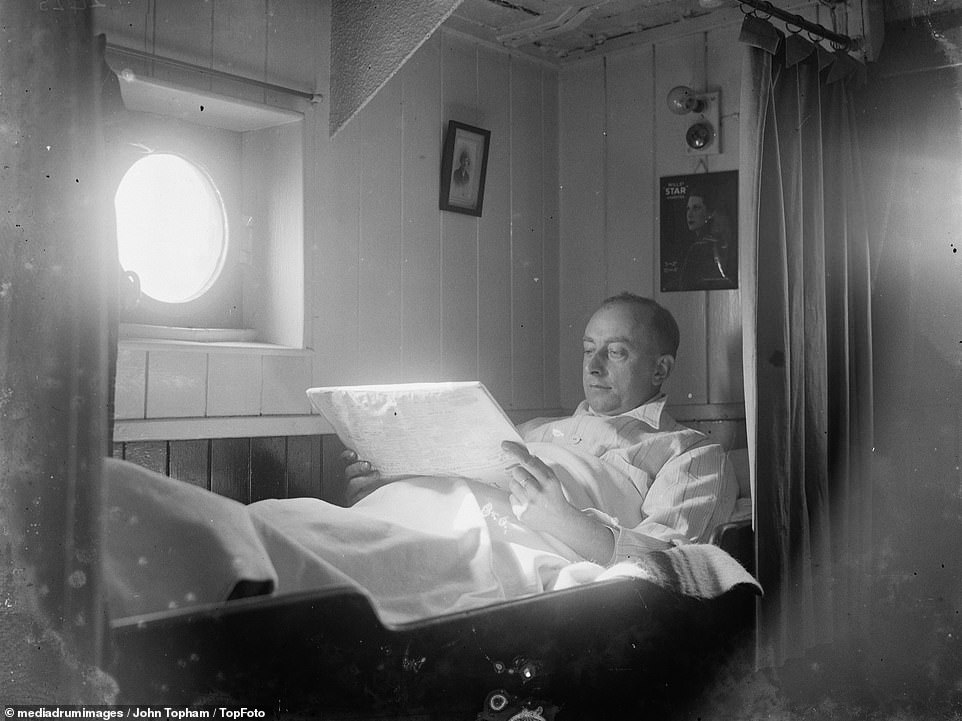

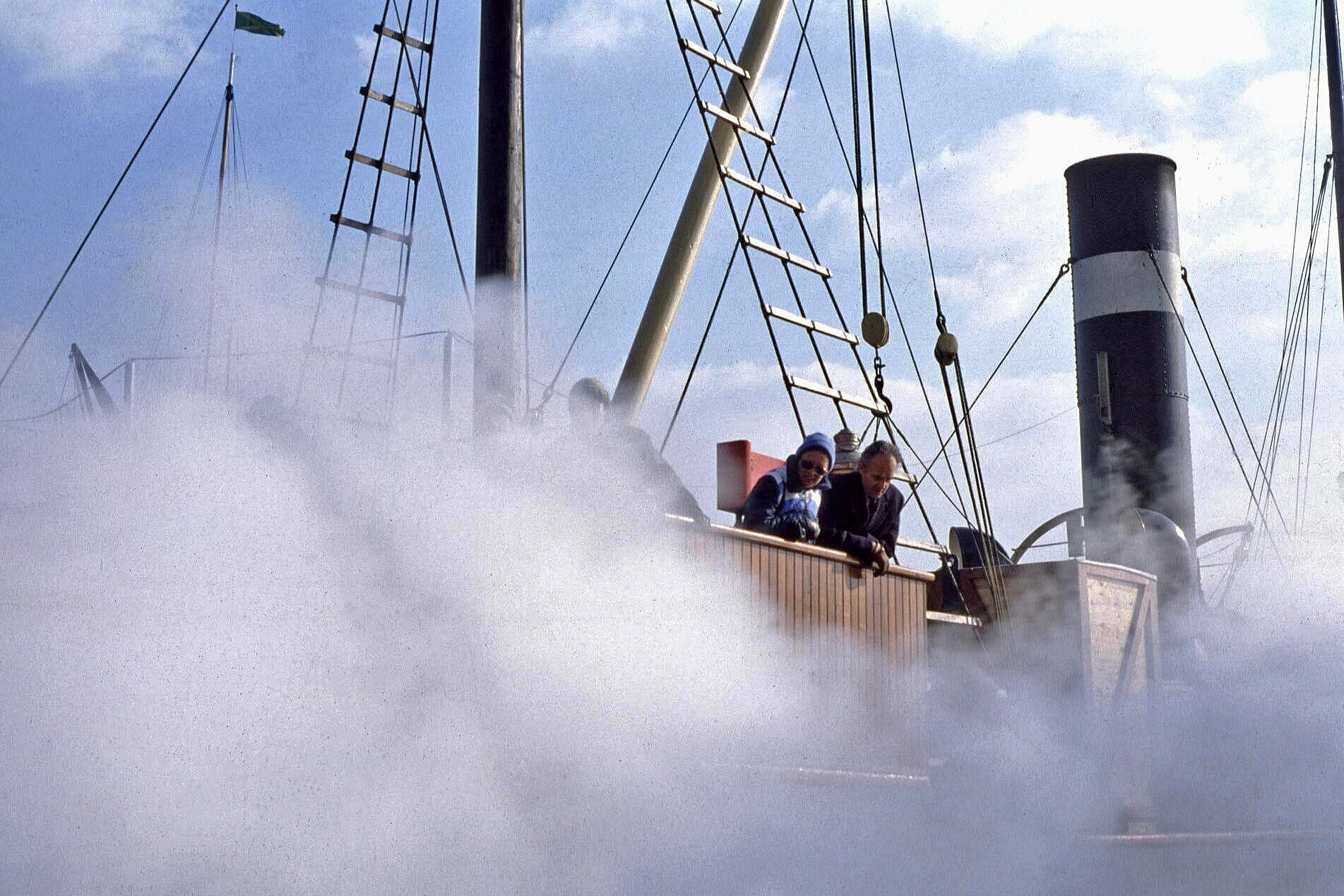

The ‘SS Eston’ ‘tramp’ steamer shown below was built in 1919 and though a larger ship of slightly different design she helps illustrate what life was probably like onboard SS Robin when at sea. Whilst some of the pictures are posed, all were taken on a voyage from Woolwich in London to France in 1938. The Eston was torpedoed and sunk in 1940 with the loss of all 18 crew, a fate shared with over 30,000 other seamen and some 2,500 ships in the merchant service in WW2 and over 5,000 ships in WW1.

Born in London

Orchard House Yard in red on banks of River Lea at Bow Creek. 1899

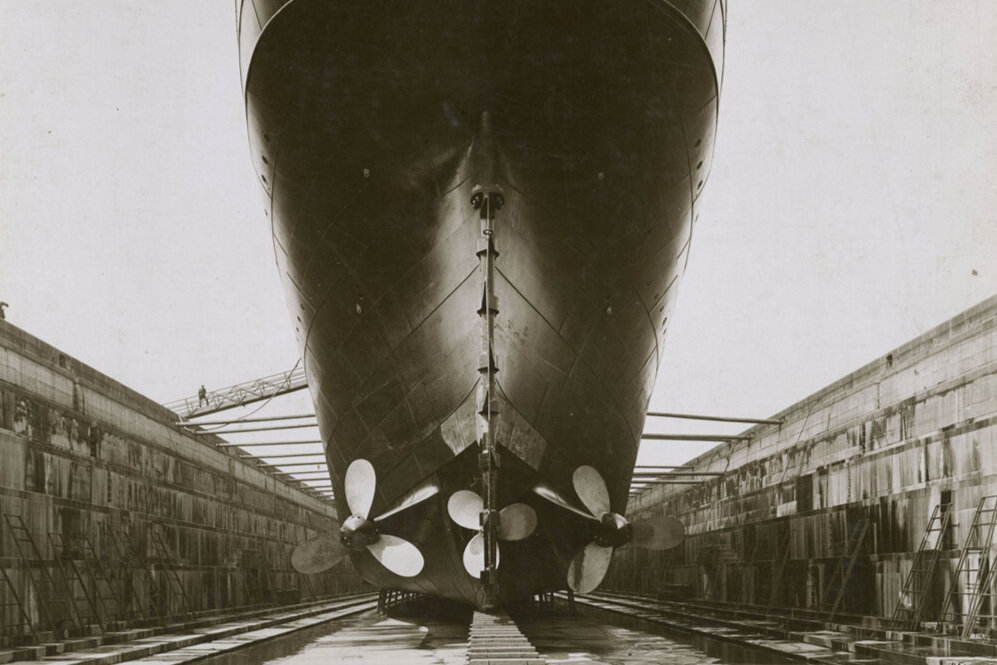

Laid down at Orchard House Yard at Bow Creek, Blackwall, London, in December 1889, ‘Robin’ and her sister ship ‘Rook’, were launched after some challenges into the River Lea where it joins the Thames in August and September 1890.

Ordered speculatively and probably at low cost by Robert Thomson, a shrewd ship broker and owner in the City of London, both ships were constructed on slipways built by Ditchburn & Mare in 1845 and later owned by the famous Thames Iron Works and Ship Building Co who leased the yard to shipwright William Jolly a Thames barge builder. He started construction before selling the business shortly after to Mackenzie, McAlpine and Co. Both builders were inexperienced, probably ill equipped and struggled to complete the orders to a high enough standard to satisfy Lloyd’s special survey.

Eventually Thompson took over the work himself, paying a naval architect superintendent to complete the ships on his behalf to Lloyd’s highest class of 100A1.

Robin and Rook were to be the last ships built at the yard which closed immediately after.

Sent to the East India Docks nearby for final fitting out, Robin was later towed to Dundee where Gourlay Brothers & Co Ltd installed her boiler, triple expansion engine and ancillary machinery. Rigged as an auxiliary three-masted schooner she was designed to carry sails when needed. She was registered in London on completion.

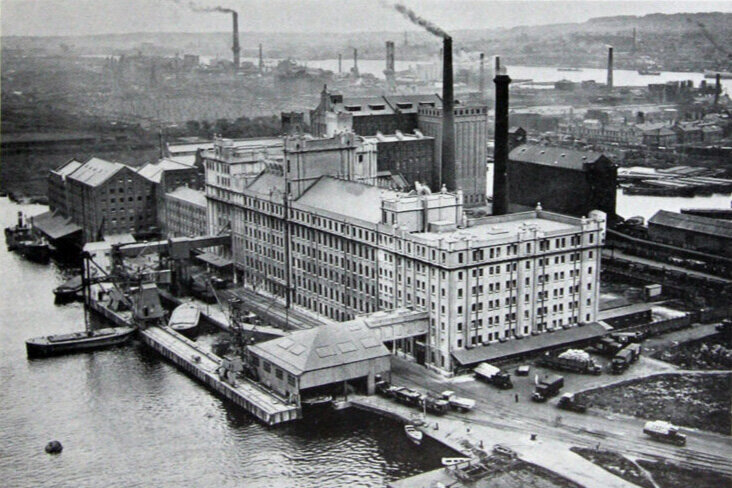

Bow Creek and the banks of the Thames; from Deptford to Woolwich, had not long before been considered the world centre for shipbuilding with a proud tradition going back many hundreds of years, supporting the capital as a global trading empire and supplying the bulk of the ships used in the Royal and Merchant Navies. The Thames Iron Works was one of the largest yards in the country, building the biggest ships either side of the River Lea at Bow Creek.

By 1890 newer ship builders in Scotland and on the north east coast with lower overheads had become fully established and had taken over the market, causing the yard to finally close in 1912. This brought large shipbuilding to an end in London and few smaller yards to go into a steady decline from which they never recovered.

Subsequent bombing in World War 2, development and urban regeneration have largely cleared the area of its maritime past. Trinity Buoy Wharf Lightship Depot and the basin of East India Dock remain as important reminders and are shown as green above.

Robin survives as one of very few London built ships left of this incredible era.

Maiden voyage and crew

SS Robin at Coleraine Quays, Ireland c 1897

Sold into service with Arthur C Ponsonby & Co of Newport, South Wales. Robin’s maiden voyage began in 1890 when her crew of twelve signed on at Liverpool for a passage to Bayonne, in south-west France, probably to carry out coal and bring back pit props for the coal mines of Wales. Crewed by a master, mate, two engineers, four firemen and four seamen, life aboard was hard with crew living in the most basic of conditions.

Forward crew accommodation comprised of a simple table, benches, wooden bunks and mattresses of straw known as ’Donkey’s Breakfasts’. Sharing their space with the anchor chains coming down from deck they would eat their meals by the light of oil lamps. In contrast the master’s cabin was furnished with a polished table, settee and chair. Lit by a brass gimballed lamp it also contained a hand washbasin in a wooden cupboard; a gallon toilet can to carry water and a container to catch the water from the basin. Simple food was cooked in a coal fired galley on deck.

Pay for the Master was £2 5s per week with crew at £1 0s who also had to find their own provisions, as a cook was rarely signed on in the UK until after the Second World War. Crew turnover was high, with men staying barely two weeks aboard between ports, but master’s tended to stay on for a year or more.

Robin’s second voyage began at Swansea in 1891, taking her to Rouen, the Mersey, Plymouth, Deauville, Guernsey, London, Rochester, Newport, Bristol, Swansea, Cherbourg, and back again to the Thames.

This was to be her pattern of trading for the next ten years; mainly between the seaports of Britain and Ireland, with side trips to continental ports, carrying bulk cargoes of grain, coal, iron ore, scrap steel, china clay, and railway rail, as well as general cargoes of casked and baled goods, even granite blocks for the Caledonian Canal in Scotland.

Loading at this time still relied on dockworkers or stevedores to manually handle cargo coming on or off when in larger ports. The ships crew often did the job themselves when at smaller wharves. They were assisted by the ships ‘derricks’; cranes attached to the masts with steam winches which could move cargo via the hold and shore, lifting it up or down using buckets or rope, chain and slings.

Film of Thames Ironworks battleship ‘HMS Albion’ being launched into River Lea from the north bank in 1898. Orchard House Yard is at center left, to the south west.

Pictures of SS Eston, a typical steam coaster built 1919 showing crew life aboard.

Sold on to Spain

SS Robin’s second owner the Hon. Arthur C Ponsonby on his Brecon Hunt Cup winning horse ‘Isabel’. C 1900

In 1892 Robin was sold to the West of England & France Steam Navigation Company, who within a few months sold her on to Alexander Forrester Blackater of Glasgow who registered the ship at his home city. In 1896 following an engine breakdown she was towed into Plymouth with further repairs recorded in London in 1899.

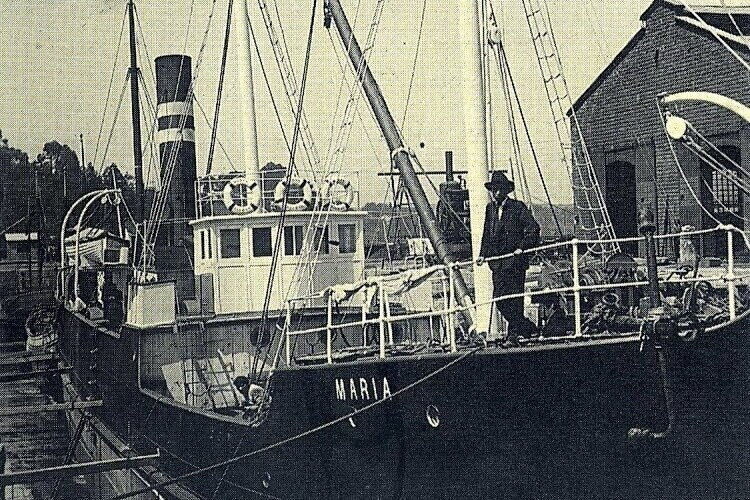

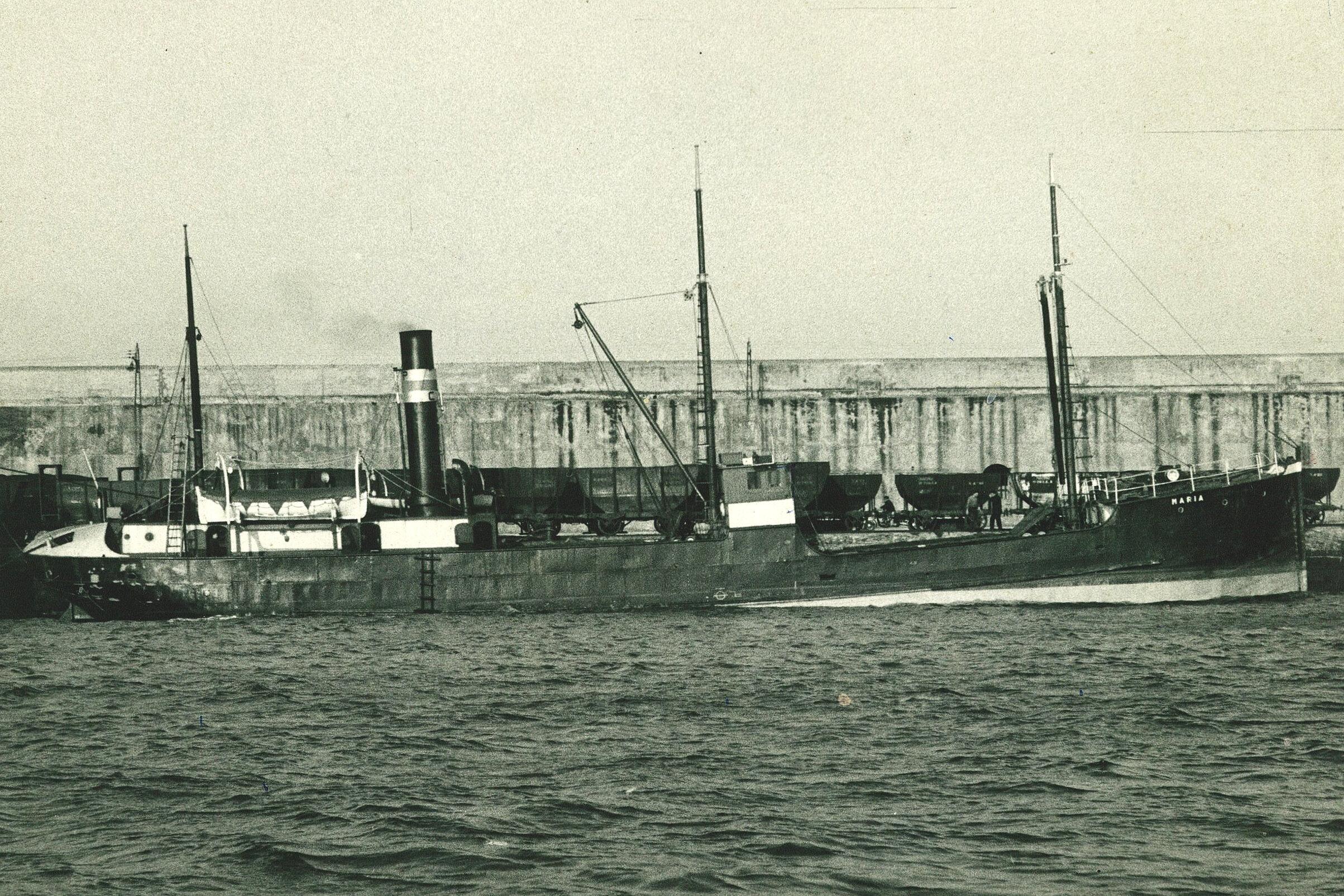

Sold on 17th May 1900, but this time to Spanish owners the Robin left the U.K. from Liverpool for the last time. Taking a new name ‘Maria’ after the mother of the five brothers who owned the company, she was to become registered in Bilbao.

The company Hermanos Blanco Fábrica de Sidra, later Sidrería Blanco, Saro y Cía, used her to transport apples to their cider making factory at Ribadesella, Asturias and carry the finished cider, Calvados and some other spirits out to distributors and customers on the Atlantic coasts of France, Belgium, England and even Norway until 1913-20.

During the 1914-1918 War she carried iron slabs for the French Government from a foundry at Santiago to Bayonne and Bordeaux, escorted by two navy destroyers to protect her from German U-boats.

Later sold to Hijos de Angel Perez y Cia S.A. she was used to transport coal from Gijon to Santander for the bunkers of the liners owned by Cia Transatlantica Esanola S.A.

In 1929 during a gale she broke from her moorings at St. Jean-de-Luz and was stranded ashore with hull damage amidships. Her crew of six luckily being saved.

From 1930 she carried coal, iron ore and general cargo to ports in northern Spain; mainly Gijon, Aviles, Santander, Bilbao and Pasajes. Laid up for much of 1932-36 due to a slump in maritime trade, she sailed in 1934 but ran aground at Bayonne becoming stranded alongside a quay. A week later she struck the jetty at Adour and was holed in two places, beached at Montbrun to prevent her sinking she later broke her moorings, capsized and sank. Salvaged and repaired, her wheelhouse fitted a few years before, may also have been replaced at this time. In 1935 she was sold briefly to Mr Diaz Romeral of Castro Urdiales.

In 1936 she was commandeered by the Spanish Government until General Franco’s forces took the port at Santander in 1937.

Reverting back to A. Perez y Cia S.A she carried coal to ports in the north of Spain until 1942 after which she was put out to charter to several firms and used to carry coal from Aville, Gijon and San Esteban de Pravia to Bilbao and Vigo. Return cargoes were of iron ore from Bilbao to Gijon and timber from Corcubion and Noya to Gijon with occasional general cargoes between Gijon and Pasajes.

In 1962 she broke her propeller shaft, possibly losing the propeller and had to be towed by a fishing boat into Corunna for repair with a new propeller and shaft fitted.

Between 1964-66 she mostly carried coal from Gijon to Bilbao with iron ore on the return trip.

Last of the line

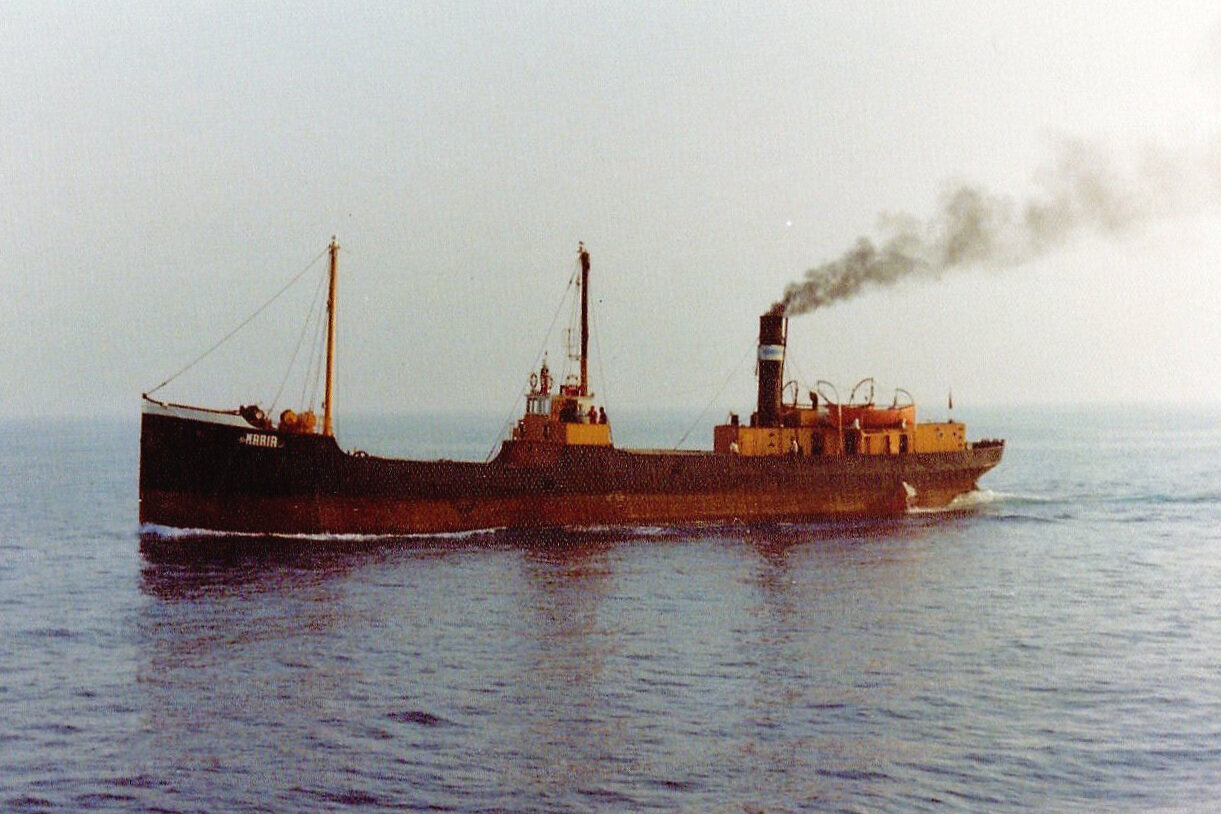

As SS Maria in last months of service. Bilbao c 1974

In 1965 Maria was sold to Eduardo de la Sota Poveda of Bilbao, who over a few years was to carry out the first major alterations to her structure since her launch in 1890.

By now tired and showing her age, major repairs were needed to her hull which also needed strengthening to withstand heavy seas. Her whale back covering the aft deck and mizzen mast were removed, the fore mast, main mast and funnel were shortened and the forecastle accommodation was extended. Her coal fired boiler was converted to oil firing and oil tanks were installed in the coal bunker spaces. The watertight bulkhead between the cargo hold and boiler room was moved aft to give more cargo space. Cabins, toilets and crew facilities were replaced or upgraded and steam driven electric generator and lighting installed.

After her refit she sailed carrying coal from Gijon to Bilbao and iron ore from Bilbao to Gijon for another nine years.

Maria at 84 years of age discharged her final cargo at Bilbao in 1974. With her owner expecting delivery of a new vessel she was laid up ready to be sold for scrap.

By this time Maria was unique, having outlived thousands ships of similar design and age which had been destroyed in the preceding twenty years as obsolete or sunk in two World Wars as a result of bombing, mines and torpedo attack.

Her fate should have been sealed but incredibly the Maritime Trust based in the UK recognized her significance and with financial support via the Science Museum, saved her at the last moment from the breaker’s yard to preserve her for future generations.

Still in working order, she left Bilbao on the 12 June 1974 and returned back to Britain under her own steam.

Cradled out of the water at Doust & Co’s Slipway yard, at Rochester for repairs, she was later restored over several years and returned back to her original appearance as far as practicably possible and given her original name.

Hull repairs, new masts of timber, open bridge and conversion of hold space for visitor access all being completed with the help of volunteers at a time when it was very difficult to raise funds.

London attraction

Arrival at St.Katherine’s Dock. 1980

In 1980 she sailed under her own steam to London to join the Maritime Trust’s Historic Ship Collection at St. Katherine’s Dock.

By now Robin had become the worlds very last complete Victorian steamship and the only one to retain its original steam engine and boiler.

Opened to all she was displayed alongside historic sailing vessels; ‘Kathleen & May’ and ‘Cambria’, steam herring drifter ‘Lydia Eva’, Steam Tugs ‘Challenge’ and ‘Portwey’ and the ‘Nore’ Lightship.

In 1986 this popular collection was sadly closed and dispersed, due to re-development of the Dock area and lack of funds. Robin was moved to South Quay, West India Docks where she was laid up.

Funds for maintenance were limited and in 1991 she sprang a leak and it was decided to dry-dock her in Chatham for repair. During this refit a number of hull plates were cropped with new steel let in, while some plates were doubled. The main and mizzen masts, which were of wood and rotten, were replaced in steel.

On her return from Chatham, Olympia & York the developers of Canary Wharf paid for the vessel to be moved to West India Quay. This required the unshipping of the masts, funnel, lifeboats and anchor davits in order to allow her to pass under the Docklands Light Railway. Shortly afterwards the developers ran into financial difficulties and their support for the ship ceased, leaving her with no financial security. The Maritime Trust continued to carry out basic and minimal maintenance, using crew from Cutty Sark which they also saved, but was unable to find a use for the ship which could generate the revenue needed for her upkeep whilst still keeping to her original appearance.

Robin as 'SS Maria' sailing back into UK waters in June 1974 following her rescue by the Maritime Trust. Film via National Maritime Museum collection.

Fresh start

SS Robin weighing 305 tons being lifted onto Pontoon. 2010

In 2002 David & Nishani Kampfner took the vessel into their care using her as maritime museum and photography gallery and later set up the SS Robin Trust, a registered charity.

Using the ship in imaginative ways they were able to attract a wide ranging and younger generation of visitors and tap into new ways of raising funds.

In 2008 building on their success they were awarded a large Heritage Lottery Fund grant allowing Robin to be moved and extensively restored and refurbished at Lowestoft in Suffolk.

A major undertaking; much of the ship was carefully dismantled and rebuilt and in recognition of her condition, age and rarity was permanently lifted out from the water and positioned onto a new purpose built pontoon which had been specially constructed in Poland, designed to accommodate museum and visitor facilities. This radical new approach ensured the survival of the ship with the minimum of intervention to its historic fabric.

Due to the construction of Cross Rail works at Canary Wharf, SS Robin and the new Robin II Pontoon were to lose their intended home alongside the Museum of London Docklands. Instead being moved to a new temporary berth at the Royal Docks in 2011.

Sadly as result of the move and due to limited funds, the Heritage Lottery Fund were not prepared to offer a second award for the completion of interior restoration works to the ship and full museum fit out to the pontoon. This along with major changes to the SS Robin Trust board and a period of development at the Royal Docks has meant that the Trust has had to re-think all the proposals for displaying the ship in the last few years.

What next?

Robin and Robin II Pontoon on the move. 2011

In the most recent chapter of her history, SS Robin has gone into partnership with Trinity Buoy Wharf (Urban Space Management) and from 2016 various options have been explored to try and find her a new permanent home which will be suited to good public access and footfall somewhere within London.

A major step forward in 2019 has been the proposed redevelopment of the entire Royal Docks complex with reactivation of 3 kilometers of water and development of vacant or derelict land which surrounds it to create a new community and cultural destination within London.

Draft master plans are now going out to public consultation and maritime heritage is likely to be included as part of this.

The SS Robin Trust hope that SS Robin can form part of these exciting proposals, perhaps becoming the center piece of a London themed maritime heritage vessel collection.

Please sign up to our newsletters and Facebook page for latest updates.

Technical details

Hold used as photography gallery and venue hire space

SS Robin: 143 feet 0 ins (43.50 meters) Long x 22 feet 9 ins (6.91 meters) Wide

Draught 14 feet 9 ins (3.59 meters).

Gross Tonnage 366 tons, Under Deck Tonnage 273 tons, Net tonnage 176 tons.

Royal Docks viewed from the east, looking towards central London with Thames to left.

Royal Docks past and present.